Tongue, Jaws, Airway, Trouble

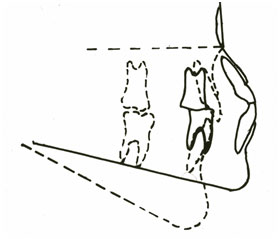

We now have learned that from Neolithic all the way through to Medieval times, our ancestors generally had well-aligned arches of teeth that wore down more than ours do today. Their tougher, more fibrous, more chewy diet and their occupational use of teeth (leather was big in the B.C. 10,000’s, and it had to be processed somehow) meant that the entire crowns of their back teeth were worn away by age 40-50, if they survived that long. In addition, their jaws grew differently than ours do today. Our ancestors’ upper jaws grew much wider, and their lower jaws tended to grow more forward and less downward than ours do today. This tracing, created by Dr. Michael Mew from compiled measurement data, shows the difference for us:

The solid line represents our ancestors, and, yes, the dotted line is most of us today. Downward, not forward.

This modern growth pattern leads to crowded, misaligned teeth, lack of space for wisdom teeth to come in, and a less prominent lower face than our ancestors generally possessed. These are objective, precisely measurable conditions. Esthetics are a far more subjective thing, but even so, many of us would often agree that folks with well-developed jaws tend to be good-looking.

There are other effects of poor jaw development, though. More damaging effects than we might first imagine:

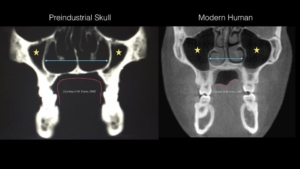

Consider our tongues. They are highly muscular. We put them to work constantly, when eating, speaking, kissing … Our tongues need a nice big house to live in. But when our jaws don’t grow wide enough, nor forward enough, our tongues don’t have enough space to live. Breathing is affected negatively by this. We now have firm, reproducible data that teach us that when the jaws are underdeveloped and the tongue lacks room to live, the airway is then constricted. It grows too small, and the life-sustaining act of breathing is compromised.

These two MRI images summarize the whole story. The outline of the tongue is in red in each image:

What a contrast! The preindustrial human’s tongue inhabited a mansion in the Hamptons; the modern human’s tongue is crammed into a phone booth.

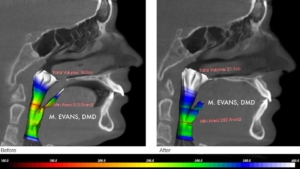

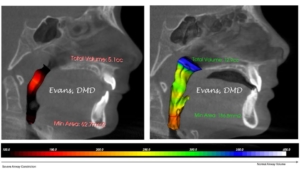

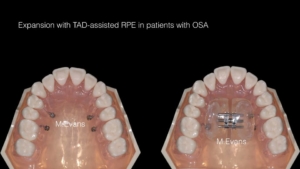

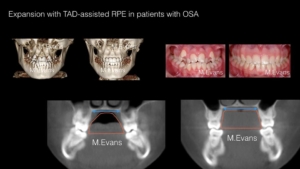

Dr. Marianna Evans of Newtown Square PA has excellent, reproducible MRI data that shows the child’s airway increases significantly in diameter and volume when underdeveloped jaws are expanded and led to grow properly via early functional therapy. This treatment would ideally be around the age of six to eight.

In each case, the images were taken about 18 months apart. Note the significant increase in airway volume. Also, note the more upright, less slanted positions of the front teeth as seen from the side, and the increased bone thickness to the lip side of those front teeth.

Constricted, under-sized airways are a serious health concern. They are a major cause of Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) and its more threatening cousin, Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). These two diseases cause significant morbidity and mortality in the adult population, and are not kind to children either, as we shall see.

According to the American Thoracic Society, “Sleep-disordered breathing is an umbrella term for several chronic conditions in which partial or complete cessation of breathing occurs many times throughout the night, resulting in daytime sleepiness or fatigue that interferes with a person’s ability to function and reduces quality of life. Symptoms may include snoring, pauses in breathing described by bed partners, and disturbed sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is by far the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing, is associated with many other adverse health consequences, including an increased risk of death.”

Due to the complexity of modern human life it’s difficult to determine just how much OSA contributes to death due to cardiovascular diseases, automobile accidents and other causes. The effects are certainly severe though. Marshall et al. in The Busselton Health Study in SLEEP, 2008;31(8):1079-1085, conclude: “Moderate-to-severe sleep apnea is independently associated with a large increased risk of all-cause mortality in this community-based sample.”

We thus have a probable cause-and-effect relationship that goes like this:

Reduced dimensions of jaw development — Decreased airway diameter and volume — Sleep Apnea — Increased mortality

In adults, according to the American Sleep Apnea Association, the Mayo Clinic and many other reputable sources, Sleep Apnea causes daytime drowsiness, nighttime insomnia, snoring, dangerous episodes of breathing cessation during sleep, headache, irritability and difficulties in paying attention. Further, the gold standard of treatment for Sleep Apnea at present is wearing a CPAP device during sleep. In other words, dressing up like Darth Vader every night.

In children, Sleep Disordered Breathing and Sleep Apnea have somewhat different effects. The American Sleep Apnea Association has this to say about it:

“Studies have suggested that as many as 25 percent of children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder may actually have symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea and that much of their learning difficulty and behavior problems can be the consequence of chronic fragmented sleep. Bed-wetting, sleep-walking, retarded growth, other hormonal and metabolic problems, even failure to thrive can be related to sleep apnea. Some researchers have charted a specific impact of sleep disordered breathing on ‘executive functions’ of the brain: cognitive flexibility, self-monitoring, planning, organization, and self-regulation of affect and arousal. Several recent studies show a strong association between pediatric sleep disorders and childhood obesity.”

The possibility of a relationship between limited duration of nursing, soft diet, underdevelopment of jaws, reduced airway volume, Sleep Apnea and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one that demands further rigorous scientific research.

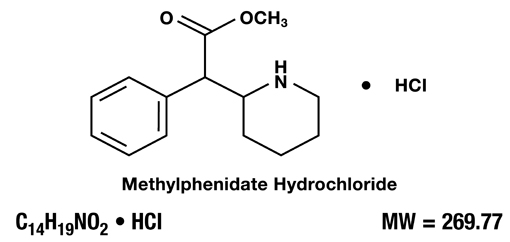

The current treatment of choice for ADHD is the use of stimulant medications.

How much better would it be if even some cases could be prevented by means of early orthodontic intervention?

We now begin to understand the stunning advantages of achieving healthy jaw and airway development, starting at birth and continuing to the adolescent years.

How is this done? When is this done?

The relatively few orthodontists I know who are advancing dental science in this area assert that they prefer to see all children for a screening examination at age six to eight. Surprisingly, age twelve is late in this treatment philosophy.

The treatment is complex, tailored to each case and constantly evolving, and I am not an orthodontist, so I will limit my comments to generalities. For upper-jaw width deficiencies, the well-known palatal expanders are an integral part of most treatments. These are actually quite well tolerated in the six-year-old patient, and palatal expanders provide highly predictable, consistent treatment outcomes.

Achieving forward growth of the mandible, when indicated, is a more difficult goal to achieve. One method is Biobloc Orthotropic postural appliances. These are capable of non-surgically increasing posterior airway dimensions through sequential advancement of both the mandible and maxilla with a series of removable acrylic mouthpieces.

These treatments may seem odd to us at these young ages. Yet four striking advantages often come out of early orthodontic, indeed orthopedic, jaw development: increased airway volume, decreased total treatment time, decreased total treatment cost, and better, more robust bone support for the teeth. This means less chance of gum recession later in life.

Think about it. Ideally, by age eight or nine, your child’s jaws are now growing wide enough and long enough to accommodate all of her teeth. There’s enough jaw length for every tooth, including those dreaded wisdom teeth, to fit within her bones and soft tissues. There’s enough jaw width for her teeth to erupt without causing damage to their own bony supporting apparatus–damage that is the primary underlying cause of gum recession later in life. (If there isn’t supporting bone, or if it’s very thin, the overlying gums are going to recede.)

With proper, ideal jaw development, thirty-two teeth can fall into place and require minimal guidance in the middle school years. Thus, the course of orthodontic treatment potentially changes from two-plus years of frequent wire-tightening, into an efficient process where the child has a few months of treatment between age six and eight, and then six months or so of treatment later on. Again, each case is unique, but this is how the new treatment process generally tends to go.

It’s not entirely too late in adults, either. Progress is being made in making reasonable changes to not only teeth misalignment, but also to airway volume and symptoms related to Sleep Apnea. Orthodontics is truly evolving from aligning teeth into nice pretty curves into a vitally important treatment modality that contributes to systemic health.

I hesitate to recommend specific orthodontists in this format, but if you wish to discuss a referral, please contact our office.

I do wish to thank Dr. Marianna Evans of Newtown Square, PA; Dr. Kevin Boyd of Chicago, IL; Dr. Michael Mew of London, England, and anthropologist Dr. Janet Monge of the University of Pennsylvania for the use of their images and more importantly, for their great contributions to this developing field of medical science, which we term Evolutionary Oral Medicine.

In our last installment (for now), we shall explore what we ourselves can do to improve our jaws and the muscles that move them.

http://www.smilephiladelphian.com/now-take-your-facial-muscles-to-the-gym/